Introduction:

April 1969 in Alabama carried a gravity that extended far beyond the usual electricity of a concert crowd. Less than a year after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the nation was still raw, and the tension of that moment in American history lingered heavily inside the Montgomery Coliseum. On this night, Elvis Presley was in the midst of a highly anticipated return to live performance. Yet what endured from the evening was not a discussion of choreography or vocal range, but an unscripted act of conviction that brought an arena to a standstill.

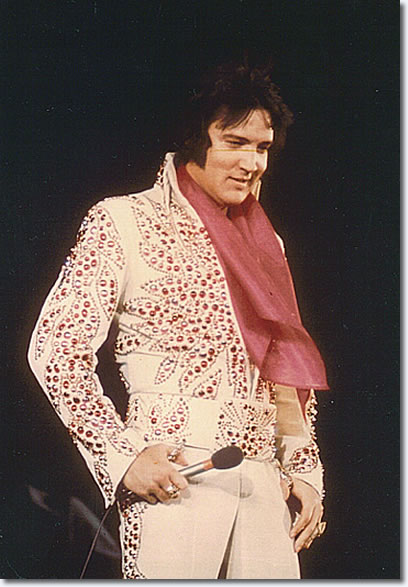

The venue was filled to capacity, reported to hold nearly 35,000 people. Fans gathered in a city deeply tied to both the legacy of the Confederacy and the front lines of the Civil Rights Movement. Presley took the stage in a white jumpsuit, performing at full intensity as he launched into Suspicious Minds, one of the era’s defining high-energy songs. Supporting him were The Sweet Inspirations, a quartet of Black vocalists led by Cissy Houston, renowned for their gospel-infused harmonies and respected work across major stages and recording studios. Their voices were integral to the sound Presley was presenting, lifting the song through its climactic moments.

Then the performance fractured. During a brief instrumental break, a racist slur erupted from the middle of the audience, loud enough to cut through the amplification and reach the stage. It was a sound many touring musicians in the segregated South had learned to brace for. The band hesitated. The Sweet Inspirations froze, the shock of open hostility filling the space with an all-too-familiar threat.

What followed had not been planned. Presley immediately motioned for the band to stop. The Coliseum fell into a dense, collective silence. Instead of turning toward the wings or attempting to defuse the moment with humor, Presley stepped forward and fixed his gaze on the section from which the insult had come. His expression was unmistakably angry.

“Stop it right now,” he said, his voice trembling with controlled fury. “These women are not just my backup singers. They are my co-workers. They are my friends. And more than that, they are my family.”

The word family carried particular weight in Alabama in 1969. Presley then made his stance unmistakable. If the audience could not treat the women on stage with respect, he told them they were free to leave. He warned that he would end the concert rather than perform under those conditions. For several charged seconds, the arena held its breath. The risk was not merely commercial or reputational. It was the unpredictable response of a crowd being confronted on race in a public space during a volatile era.

Then the tension broke. Applause began in the upper sections and spread rapidly, building into sustained approval that shifted the room from confrontation to solidarity. From within that roar, voices rose together in We Shall Overcome. It was not a rock anthem or a radio hit, but a civil rights hymn rooted in struggle and perseverance. In the middle of an Elvis Presley concert, a song of protest filled the arena.

On stage, the superstar façade gave way. Presley was visibly emotional, tears on his face. Rather than resuming the planned set, he stepped back and placed the spotlight on The Sweet Inspirations. He invited them to choose what they wished to sing, allowing them to take center stage rather than remain in the background.

Cissy Houston stepped forward, her voice wavering briefly before settling into the strength that defined her leadership. The group performed People Get Ready, Curtis Mayfield’s anthem of hope and movement, delivered with the spiritual depth that had always shaped their sound. The moment felt less like a scheduled performance and more like a direct response to what had just unfolded, with Presley’s public protection standing in sharp contrast to what Black performers often endured on tour.

“He made us feel like queens,” Merna Smith later recalled. “In that moment, he risked everything for us. He didn’t have to do that. But he did.”

The consequences followed quickly. By the next day, headlines described Presley as having taken a stand. Hate mail poured into Graceland. Promoters in parts of the South reportedly canceled future appearances without explanation. Some rural radio stations stopped playing his records, framing the incident as provocation rather than a defense of basic dignity. Behind the scenes, Colonel Tom Parker was said to be furious, concerned about damage to Presley’s brand and touring prospects in regions still resistant to desegregation.

Presley did not apologize. In the weeks that followed, he spoke more candidly in interviews about his debt to Black culture and Black musicians, with a directness that surprised critics. It was a complex truth that had always underpinned his career, his sound rooted in African American musical traditions within an industry that did not reward its originators equally. That night in Montgomery, he did not rewrite history, but he drew a line in a room full of people who understood precisely what it represented.

Elvis Presley is often remembered for spectacle, excess, and eventual tragedy. The Montgomery incident insists on another memory: a moment when the music stopped, and a performer chose confrontation over silence. As the audience filed out of the Coliseum that April night, the concert had continued, but the message carried far beyond the stage, resonating louder than any encore.